In 2020, anarchists Akihiro Gaevsky-Khanada and Andrey Chepyuk were among the first people detained in politically motivated criminal cases. At first, they and their comrades were charged with taking part in and organizing protests, even though some never even made it to any protests. Later, more and more charges under various articles of the Criminal Code were piled onto the case, and the defendants were labeled organizers and members of an “international criminal group” of anarchists from Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia. After almost two years of a so-called investigation and holding the guys in a pre-trial detention center, their trial began. It dragged on for months behind closed doors so the public wouldn’t see how absurd the charges were in a case cooked up by GUBOP (the Ministry of Internal Affairs’s anti-extremism and organized crime unit). Ten people ended up behind bars, with sentences ranging from 5 to 18 years for trumped-up crimes.

On the day he finished a six-year sentence and was due to be freed, Andrey Chepyuk was handcuffed and taken by GUBOP (anti-extremism unit) officers to Minsk for questioning over events from 15 years earlier. He was later released, placed under “preventive supervision,” and banned from leaving Belarus. A few months later, however, Andrey managed to escape.

Akihiro Gaevsky-Khanada was sentenced to 16 years in a penal colony. His sudden release as a Japanese citizen and expulsion from Belarus was the result of negotiations between the Trump administration and Lukashenko.

Today, five years after the first arrests in the case of the so-called international criminal group of anarchists, we’re launching a series of interviews with Akihiro Gaevsky-Khanada and Andrey Chepyuk. In this first part of our long conversation, we look into what it’s like to be among the first detained; to miss the surge of protest activity and its decline; to watch “generations” of political prisoners come and go and carry dozens of stories inside you; to lose hope and feel powerless because of the war in Ukraine; to be set free while your comrades remain behind bars?

_________________________________________________________________________

It’s 2025 now; you’re among the few in your case who’ve been released (Andrei Marach and Daniil Chul were also released after serving their terms). But if we rewind to 2020 and try to remember… August, the protests are in full swing, truly confrontational for the first time in many years of Belarus’s existence and of Belarusians as politically active people. Then you, Akihiro, are detained on August 12, literally three days after the election. You miss everything that comes after and see it as if through the looking glass. Andrey, you’re detained on October 2; you had a couple of months to watch the protests, but you still ended up in custody while the streets were seething and it felt like any moment everything would change, that the regime was about to crack. And you miss all of that. Did you have regrets about it? What was the mood? Did you hope for a quick change – and when did those hopes fade?

Akihiro:

The people who got imprisoned back in 2020 were running on emotion. Those who were jailed later, in 2021 or 2022, were a different story. I think the 2020 “generation” of political prisoners kept that energy. Later, when you meet them in the colony, and even now, when they’re getting out, it feels like everyone who was arrested in the summer–fall of 2020 was more charged up emotionally, even though they didn’t actually see the protests. Sometimes that takes a strange form — as you can see now, for example, with Sergei Tsihanouski: he’s still running on that 2020 charge. I had it too, and it stuck with me while I was inside. Back then, in the fall, we kept saying: a year and a half at most, and something has to happen. The point of no return was behind us; the regime couldn’t last long in that state. That’s what we thought. I even bet someone that in 2025 Lukashenko wouldn’t be on the ballot. And, well, I lost that bet.

Of course I regretted being arrested so early, especially later, when you realize the sentence will be long and totally out of proportion to what you did. You think: I should’ve ignored some caution or self-imposed brakes; I should’ve done more or at least ended up inside a couple months later. I really wanted to see that self-organization at the neighborhood level and at workplaces, to see how every sphere got politicized one way or another, how everyone was actively taking part – that surge across society.

For many years I’d thought that if mass protests ever happened, it would be a good, exciting time. And then you get arrested on one of the first days and see it all in a very limited way: through newspapers that still printed something; through lawyers who could still pass on news; through new people coming in. And by late spring 2021 it was already clear that nothing was going to work out yet.

Sure, I regretted getting grabbed so early, but I still felt like a participant in what was happening in the sense that there, inside [in prison], you can still make choices, although in a reduced form, and still take part in what’s going on.

Andrey:

I’d put it a bit differently: for me it all depended on the environment, on the vibe around me. If the cell filled up with the political “intelligentsia” – more theorists than people who actually organized or took part in protests, like reporters, bloggers, and others who were more passive about the agenda – you’d hear all kinds of opinions about the prospects and where the protests might lead. But I definitely remember a period when the street protests were winding down: as far as I recall, in November pensioners marched for a couple of Sundays, and it already felt like the protest was fading and that this was the end. Then, when the neighborhood activity appeared, it gave even more energy and faith that it wouldn’t end like that. I believed in that kind of civic self-governance, that was the ideal way for things to unfold, better than what happened on August 9–12. I liked that path; and later it really did take shape, and I was amazed at what it led to and how it looked: people just gathered and built their own infrastructure. It made me really happy, inspired me for a couple of months – probably up until the war.

At the same time, it was interesting to watch the repressive side of things. In 2020 and early 2021 in the pre-trial jail, from time to time you’d see people getting detained in groups, like ours, and it was interesting to track the trend – what charges, what groups, what criminal cases. At first they held basically everyone under a single article in one big “mass riots” case, and then they split people into separate proceedings. Later, by mid-2021, when the charges diversified and the groups did too, it got quite disturbing: you’d see more and more rare, murky articles being used. Then the procedural code changed. And the streets had already quieted down by then, activity was almost suppressed, and you could feel how everything was shifting.

As for disappointment, I’d say I didn’t feel it during my entire time in pre-trial detention. But after I was transferred to the colony, an information vacuum set in, and it got harder to analyze what was happening objectively. Too much time had passed, and it was impossible to tell what was fake news and what were real facts.

So it turns out that by analyzing your cellmates’ stories, you could track which slice of society was being detained, who was fighting and how, what charges were being brought, and what kind of sentences people were getting. You’ve got a lot of invisible knowledge that, it seems, is often underrated.

Akihiro:

Yeah, in interviews people often ask about violence, tortures, conditions in the penal colonies, and so on. A ton has already been said about that. Conditions keep changing – usually for the worse – and it’s important to talk about it so people know. Still, without seeing it from the inside, it’s hard to grasp all the nuances.

But people rarely ask how the “generations” of political prisoners changed, how the mood of the newcomers shifted. It’s one thing when it’s the people who were already activists, folks already involved in politics; then came those who just took part in street protests; and it’s a totally different story with people jailed over comments. They don’t understand why they were detained at all; some don’t even see themselves as political [prisoners].

Because our time in jail was pretty long, a lot of people passed through us, and you could clearly see these waves of political prisoners. Every time new people arrived, they’d say: “We didn’t know they were still grabbing people for the protests; we didn’t know it’s a criminal charge, we thought it was just administrative.” I look at the news now, in 2025, talk to people still in Belarus, and their relatives and acquaintances are still being detained over the 2020 protests. And in 2021 people were saying: “We didn’t know they were jailing people for protests; I just didn’t delete the photos.” And you think: it’s just a year gone by and people have already tuned out – don’t know what’s happening, aren’t cleaning out their photos and chats. Every time new people showed up, it surprised me at first; then I got used to it.

When the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, people tried to analyze how the Ukrainian state responded to the fact that in occupied or frontline areas there were prisoners who weren’t evacuated and seemed to matter to no one but their families. When you heard that Russia had launched the war in Ukraine and that Belarusian territory was used in the first days, what went through your mind about being in a confined space without really knowing what was happening and with no way to influence or control it? What did you think about the possibility of ending up in a war zone while in prison?

Akihiro:

As for the war, I didn’t really have those kinds of fears. It was more a feeling of resignation – like it became clear that our Belarusian “theater of operations,” so to speak, was being pushed to the background. At first, in our region, Belarus drew all the attention—it was the flashpoint. But once the full-scale war started, I felt that compared to what was happening in Ukraine, what people there, our comrades and ordinary civilians, were facing – everything happening in Belarus faded into the background.

On the other hand, there was not exactly hope, but a sense that because Belarus was involved in the conflict, a bad outcome for Russia might also impact Belarus and speed up some kind of change in the country.

Even inside, there was this never-ending debate: some said that if the war hadn’t started, things in Belarus would have wound down in 2022; the regime would’ve been back at the table, there would be negotiations, and people would start getting released. But because of the war, sanctions hit Belarus, it was treated as a party to the conflict, and the issue of political prisoners moved to the background. Maybe that’s how it played out. For me, though, it wasn’t so much about freeing the political prisoners specifically, as about the war potentially shaking the situation in Russia and Belarus as a whole.

Still, in the first weeks of the war, we didn’t know what was going on. There was a fear that Ukraine would be taken very quickly, that Russia would just carry out the operation and reach Kyiv, as they initially claimed. Those first weeks were really concerning: is Russia about to seize Ukraine, and will it get away with it?

Andrey:

I can still see the faces of the guards, who were really on edge. As I recall, we had some active proceedings going on then: either we were in court or the trial was coming to an end, so we saw the guards a lot. And I remember their faces: stress, fear, tension. You try to read their emotions to gauge how bad it is out there, how dangerous. Because second-hand updates on paper are one thing, but when you see raw, animal fear in someone wearing stars – that’s something else. It makes you even more uneasy, because it’s hard to grasp the depth of what’s happening, how scary it really is. When I heard the first military reports about Chernihiv – close to where my relatives live, right on the Belarus border – It felt like in that first month Belarus could easily be pulled into the war, or end up as a third party to the conflict.

Which is basically what happened: de jure they kept everything razor-thin on paper. And that was really, really frightening, because you realize you won’t be able to do anything for the next couple of years. Being locked up while your country is seeing military action is even more dangerous, even scarier, because you can’t control what’s happening with your family and your circle. It’s worse than the repression because you can’t influence anything.

Naturally the talks started: how would we live if the war spread, how would prisoners – political and not – get by; first there’d be problems with food, then communications, supply, and everything else. How would prisoners survive? We talked about that in our cell for a long time. People tried to forecast what would happen. Of course there were dark jokes that politicals would be the first to be shot against a wall. Later the war topic turned kind of surreal for me, because a lot of politicals in the colony – once the conflict became of low intensity – were spending their precious talk time on questions about Ukraine instead of asking family about their health, and so on. And you think: people must be in such a bad place if everything has slid into this kind of military obsession.

Akihiro:

It’s great when people actually ask for facts, but in the colony we couldn’t bring that up on phone calls, so everything slid into rumors. I tried to tune out the daily chatter about “the NATO Secretary General said this,” “the Ukrainians took such-and-such city,” “Russia’s losses are this many, they’re short on equipment.” It usually came with a hopeful slant: Russia is about to lose, a mutiny is brewing in the Russian armed forces, and so on. And you know that a week later all those hopes will collapse, that it’ll turn out to be made up.

The rumors got to the point where people were basically living on them, instead of coolly looking at the facts or just not wasting time on empty talk. It seemed to me that was destructive, even psychologically: over time people get disillusioned and see that everything they’ve been discussing turns out to be false.

Back to your case: this “international criminal organization” seems to appear out of nowhere. And it didn’t pop up right away – you were detained in 2020, then others were detained in other cities, apparently to collect additional testimony against you. Only in November 2021 did they designate a broad, let’s say, network of anarchists from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus as an “extremist formation.”

Everyone understands that being an anarchist in Belarus means your activity is criminalized; sooner or later it can end in detention – no illusions there. But in your case, legal lawlessness was in full swing, and you got huge sentences for earlier actions that, before 2020, were treated as administrative offenses. What’s it like to get real prison terms on such inflated charges, clearly out of proportion to what you did?

Akihiro:

Before 2020 there was a certain understanding of the “rules of the game.” If you took on some radical action or a serious initiative, you knew what you were risking, how it could be classified, you could manage the risks somehow; you knew what you were ready for and what you weren’t, what made sense to do and what didn’t. When Article 285 showed up – this “organized criminal group” case, I think it was in February 2021 – it became clear the article was crazy from a legal standpoint, especially in terms of proving anything. On paper it looked like a hard article to prove, and it was interesting to see what it would turn into, how they planned to dress it up. Then it turned out there were no difficulties at all, because there was basically no evidence. They just threw in everything that existed against us from before 2020. The key witnesses were a “legendized” (anonymous) witness from Brest Nikolai Tolchkov, an anti-extremism unit operative; and Ivan Komar, an associate of Nikita Yemelyanov, who got out in January 2022. What’s more, we found out that back in 2019 GUBOP had already submitted case materials to the Prosecutor General’s Office trying to stitch together some kind of group case, but it was rejected. And after 2021, once court practice shifted, it was clear that anything at all could fly.

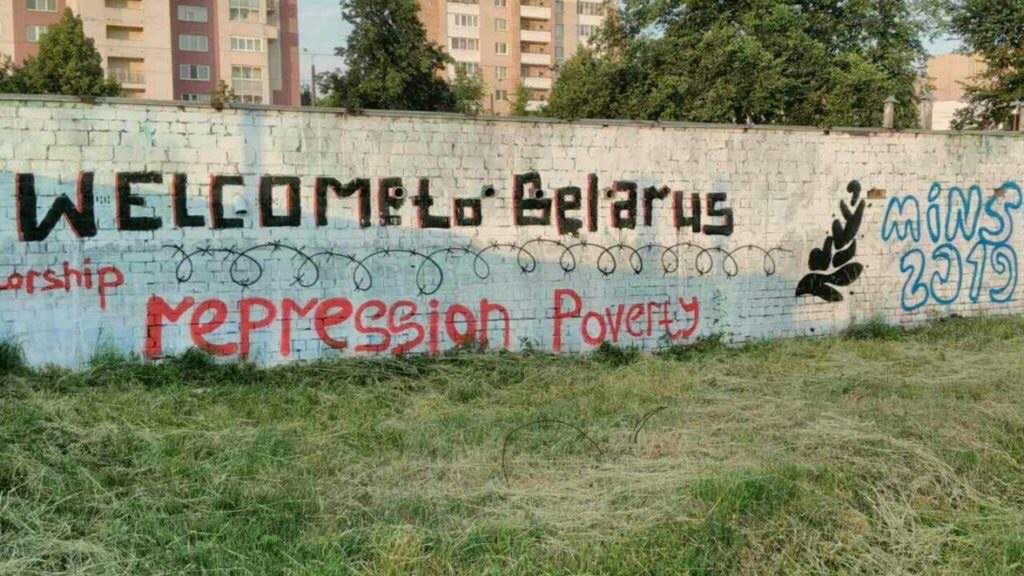

Yeah, it stung to be serving time for episodes that previously would’ve been an administrative case or nothing at all – and suddenly it’s a criminal charge. A slogan on a wall that never got anyone detained turns into an Article 130 charge. It all felt absurd. They really hung so much on us that you’re like, “Wow, what an organization, look how much they did, what a structure!” It even sounds cool. But in reality you understand they spun it up from absolutely nothing. It brought to mind those Russian cases too, like the “Network” case. I was curious how it would all develop, but in the end it was done in a really crude, heavy-handed way.

Andrey:

I’d start with the point when the case was completed [December 2021], because that’s when it became clear how the investigation (more precisely, GUBOP) put it all together. Investigator Tsybulski [head of the Minsk Investigative Committee team handling the case] was basically just GUBOP’s hands in the legal field. I was curious how cases like this appear in a broader sense, so I tried to track trends in matters similar to ours – say, the case of the so-called terrorist organization “Busly liaciać” (lit. “The storks are flying”): the episodes are worthless, just hooliganism or vandalism, yet they opened a “terrorist organization” case.

What I realized from studying the case file was that GUBOP was just collecting anything at all, showing “activity,” registering all those operational-search measures, knowing they’d be given a green light later to turn it into something. They just kept collecting and collecting. I wouldn’t be surprised if they also pushed for changes in the procedural and criminal codes, trying to sow the idea in society, and not only in society but in backroom talks in the prosecutor’s office and at Lukashenko’s briefings, that we had a very dangerous extremism/terrorism situation and the laws needed changing; that there were some criminal cases and some people detained on such-and-such charges. They needed changes so all those materials and all that “activity” could be conveniently funneled to court, so the whole system would run smoothly, so the investigation could hand everything to the prosecutor’s office without any issues or delays, and the prosecutor’s office to the courts, without worrying whether the court would send it back for revision. That’s basically how it went after the changes to the procedural code. I think it was a big, joint enterprise by GUBOP and the KGB together with the prosecutor’s office.

As for our sentences and charges, I saw it the same way many others did: you have specific actions that used to carry one set of penalties, and now you realize you can get 10–12 years behind bars for a hooligan act. Sitting in detention, I understood that a post or a piece of graffiti could cost me roughly five years of my freedom – and my priorities shifted. You see there’s not much you can do anymore, so you start thinking about other things: your family, your loved ones, comrades who are still free and facing the same fate. You think: as far as I’m concerned, it’s basically already decided – so how do I make sure fewer people end up in this situation? You try to shift the focus away from yourself to something else; it calms you down, and it gets a bit easier.

Four years later, on July 15, Autonomous Action “Belarus,” Indymedia, and Mikola Dziadok’s blog and social media were designated “extremist formations,” with the authorities pretending they’re all “subsidiaries” of your international criminal group. How did you react to that, given the case isn’t forgotten or shelved but has effectively become a springboard for tacking on new cases? And since your comrades from this case are still imprisoned, what do you think their prospects are?

Akihiro:

Andrey talked about how the security services might have pushed legal changes to make their work easier. Before 2020 there were plenty of rumors that GUBOP might even be disbanded, that people were unhappy with their work; there was conflict between them and the KGB, each trying to squeeze the other. Former officers I did time with confirmed that this was a real possibility.

In 2020 GUBOP basically gave itself carte blanche and racked up political points. 2020, in a sense, saved them. And these big cases they started slapping together let them work forever. Like now the Investigative Committee and the Ministry of Internal Affairs can endlessly find new people over comments, donations, and the 2020 protests, because there are tons of photos and comments. The only check there is the statute of limitations. But with a “criminal organization,” there’s basically no limitation period: they can claim a person belonged to it right up until 2020. In our case, someone allegedly did something in 2016, then never got in trouble again, and by 2021 the statute on that episode – say, hooliganism – was expiring. And they’d say: “No, you belonged to a criminal organization until your arrest in 2021.” And there’s nothing to prove. Now that they’ve added Autonomous Action and Indymedia into it – that’s beyond a joke. On the other hand, take Mikola Dziadok: he initially got a short sentence, and I constantly worried it wouldn’t end there. In a way, getting a huge sentence is “easier,” because you don’t process the numbers – 15, 16, 20, 25 years all feel like the same order of magnitude; you hope they’ll all end around the same time because events will happen and things will change, and those with long terms will be set fee. With short terms, there’s more fear it won’t be over, they’ll just add more time. It’s insane, and as far as I know there aren’t other political cases being spun up like this right now; it’s still a unique one.

As for the prospects for the guys behind the bars, it’s hard to say or predict anything. Even two months ago it was hard to say anything concrete about myself. There are lots of factors we don’t know; probably no one knows what’ll happen. Compared to before – when anarchists weren’t always recognized as political, or it took ages – anarchists were never a priority. Now there are lots of high-profile media people, rights defenders, journalists who are top priority, and then there are the “radical” anarchists, but at least everyone’s being recognized as political prisoners. Of course there’s still hope someone might get out early, but, sadly, there isn’t much optimism.

Andrey:

Honestly, I was surprised that Investigator Tsybulski is still on the job and that the mechanism they tested on us is still in use. When they brought me to see Tsybulski after my release, everything was just like in 2020: Tsybulski looks much worse than the last time I saw him, but it was the same case, the same questions from the “criminal organization” file, the same rhetoric. That’s when I realized they’re simply using the same mechanisms – they just need to put someone behind bars. Same playbook, same work.

As for the case itself, they’re just using their legal levers. If there’s an earlier, ready-made case, they don’t need to prove anything. In our criminal file there’s the 2010 case against Frantskevich, Dedok, Olinevich, and others. They don’t have to re-prove what was in the 2010 case in the context of ours. They’re doing the same thing now: on the basis of our 160-volume case and the 2010 case, they tack on additional “formations,” organizations, and so on – without proving context or anything else. They’re just exploiting legal mechanisms that let them do this for whatever immediate goals they have – say, to lock up Dedok or extend his term. As far as I know, he himself didn’t expect to be out in five years; that’s a short term. Sure, the situation was different then, no war, etc., but even back then he understood they’d spin it up anyway, because such a relatively short term looked strange given the context and who he is.

As for our comrades who are still imprisoned, it’s very hard to assess. When I got out, for the first few days I didn’t even know which of my co-defendants were already free. I was surprised Akihiro was under a “prison regime” (as opposed to a penal colony), because I didn’t know that while I was in the colony. Information barely reached me, let alone those on strict or prison regimes. So it’s hard to judge, but I really hope people are doing okay mentally and physically, that the system hasn’t managed to crush them or cause serious harm.

I don’t think we should expect something horrible like the deaths of political prisoners. I hope the Department of Corrections controls that, doesn’t allow people to become disabled, and prevents terrible incidents, because, absurd as it sounds, it’s responsible for its “special contingent.” Many will disagree with me, probably. But I hope that the attention to political prisoners from all sides – the Department of Corrections itself, the public, and from abroad – will have a positive effect on everyone, including our comrades.

Andrey left the colony after serving his term, while Akihiro’s release took everyone by surprise. These days, though, anyone who walks out can’t be sure they’re truly free – It’s like Belarusian roulette: some end up back in the crosshairs, others don’t. You and your comrades were part of the same case: some got longer terms, some shorter; some are released earlier, others aren’t. What’s it like to step out, knowing others are still inside?

Akihiro:

Every political prisoner has their own story. Some had individual cases, some were more politicized, some less; some got caught up “by accident,” so to speak, and didn’t plan to do anything political after release, and still don’t. I think those who were involved in activism before 2020 expected repression and knew they might face it, so nothing ends at the moment of personal release.

And in general, people on the outside aren’t always freer than those inside. A lot of people you know – comrades you did things with, or people you know of in a good way by reputation, even beyond political prisoners, just prisoners in Belarus overall – are in a state of rightlessness. Even if every political prisoner were released, the prison problem would still remain. There are tons of absurd cases; people are locked up for who-knows-what, and no one even hears about them. At least political cases get talked about (and even then, many aren’t on any lists). There are people with no hope that anything will change, unless an amnesty happens to touch them, yet nothing is improving for them in any broader sense. And when you know your comrades are still there, then for someone like me, who got more than 10 years to serve and, by some stroke of luck, ended up free, that puts a certain burden of responsibility on.

Do you deserve this [release] or not? What can you do to help the people who are still inside? Is there anything genuinely useful you can do now, especially from abroad? There’s definitely some confusion there. But you also realize you definitely won’t be staying on the sidelines, because nothing is over yet. That’s how I see it.

Andrey:

Yeah, “Belarusian roulette” is a beautiful phrase – spot on. But I wouldn’t call everything above “responsibility,” because responsibility, to me, is something else. As pompous as it may sound, it’s more about duty: when you’ve shared all of this anxiety, stress, suffering in all those institutions. I didn’t live through the times when political prisoners were kept in temporary detention centres crammed to the brim, with bedbugs. I was lucky: I caught that [volunteer] camp outside Akrestsina, heard the protesters shouting “Let them out!” and “Long live Belarus!” I was in slightly different, much better conditions, managed even to receive a care package. And still, when you share all those hardships with hundreds of people, spending more than a year in pre-trial detention, a lot of people pass through: some get detained, sentenced; some get released. After that, once you’re out, it’s very, very hard to be indifferent to the fate of those who are still inside.

My personal view is that we should help however we can not only political prisoners (though first and foremost those with whom you share ideas and a worldview), but also people convicted in absurd cases. I think it’s right, it’s needed, it’s necessary.

At the same time, after such experience, I can understand those who won’t want to share the burden, won’t want to help someone, won’t show solidarity, and will just focus on their own lives. That’s absolutely normal, and no one should be forced into such actions or judged through a lens of misunderstanding.